Why is Finding a Job So Hard for Holden Caufield?

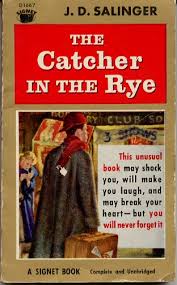

As many will recall, the hero of The Catcher in the Rye,

Holden Caufield (age 17), spends a three nights in Manhattan right after

getting kicked out of yet another prep school. Holden is a very

sensitive guy who's a "hell of" an observer of the human condition. Salinger's naturalistic language, his ability to tell

an action packed story with scores of  digressions

(all of which actually relate to the plot), and the profound

maturity of the book's themes have conspired to make The Catcher a

permanent classic since its release in 1951; it continues to be one

of the top ten most banned books in the United States.

digressions

(all of which actually relate to the plot), and the profound

maturity of the book's themes have conspired to make The Catcher a

permanent classic since its release in 1951; it continues to be one

of the top ten most banned books in the United States.

In one scene, Holden's sister, Phoebe, presses him to state what he wants to be; does he want to be a scientist, a lawyer maybe? What does he want to be when he grows up?!

Finally,

he answers: "I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game

in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and

nobody's around -- nobody big -- except me. And I'm standing on the edge of

some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if

they start to go over the cliff -- I mean if they're running and they

don't look where they're going I have to come out form somewhere and

catch them. That's all I'd do all day. I'd just be the catcher in the

rye and all."

Now, unless one does some re-framing of other professions like teaching and nursing and firefighting, there aren't a lot of jobs opportunities out there for catchers in the rye. It's a systems problem in the sense that there are lots and lots of people who want to do things that the systems that they are embedded in don't really accommodate.

A very smart guy in the systems thinking field, Barry Oshry, has done a lot of thinking, writing and intervening regarding the ability of systems to embrace lots of

| Barry Oshry |

1. Integration,

i.e., the degree to which a system has a shared objective/mission that

everyone in the system understands and adheres to in some fashion.

2. Differentiation, i.e., the degree to which a system has different ways of interfacing with the environment.

3. Homogenization,

i.e., the ubiquity of norms, mores, behaviors, information within a

system; the degree to which everyone does and knows the same thing,

such as speaking the same language, possessing shared mythology,

dressing in some way that others experience as appropriate, and

4. Individuation,

i.e., the degree to which a system allows and enables individuals to

be freely themselves and express themselves as most befits who they

are.

Some illustrations:

A great orchestra can be a highly robust system. There's a shared mission of producing great music that honors the creativity and inspiration of the composer. There are many different types of music that can be played and the system can be subdivided in many sorts of ways to interact with its audiences and its larger environment (chamber music, quartettes, full orchestra symphony, public performances, private concerts, recording sessions, visits with the media, political events, etc.). Everyone knows the score, i.e., they all know the scales and they wear a uniform that enable everyone looking at them to say, "Oh, I must be at the symphony!" And, they can tolerate and encourage a great range of individuality. Really good musicians get to do what they're good at, what they really most want to do.

Rigid systems don't have this sort of pliability. They require people to hoe the "party line", for example. You can never do enough to demonstrate what a believer you are in whatever the system's doctrine might be. Rigid systems tend to be simpler systems in that they don't have a lot of differentiation, i.e., they do a finite set of things in relationship to their environment and they don't easily generate new modalities of activity. They are also seriously into conformity. People dress the same, talk the same, and know pretty instinctively how not to get out of line. (Think North Korea and the Taliban.) As you might expect, rigid systems are also not big on individual freedom and expression...unless you're natively the type of person who really likes to pound the drum in just exactly the way the rigid system wants you to.

Inchoate systems are big on differentiation and individuation. Everyone gets to do h/er own thing and there are a zillion small groups that are really adamant advocates for what they want and really adamantly antagonistically against what some other group wants. (Think of the litigious conditions of the U.S. or the political blogosphere.) Unfortunately, inchoate systems tend to have too little integration and homogenization. No one agrees on any core principles and there are no overarching norms or information bases. So, everyone is sure that they are right, but the system as a totality isn't moving along any particular pathway.

Art of the Future concentrates on the design, creation and maintenance of Life Sustaining Organizations, those organizations that recognize,celebrate and promote the vitality of the people comprising the organization, of themselves as living systems and the natural ecology supporting us all. As living systems, life-sustaining organizations emphasize the importance of protecting and fostering both logic and creativity in all manifestations.

Sensitive, thoughtful, aware people, like Holden Caufield, can thrive only in the context of life-sustaining organizations. Knowing they need catchers in the rye, these organizations honor those

who step up to the role. As organizations evolve from mechanistic to organic sef-perceptions, may we be fortunate enough to be associated with those open to such possibilites. May we be courageous and diligent enough to assist in their creative evolution.

References: Barry Oshry: Seeing Systems (2007) and Leading Systems (1999); Michael Sales, "Understanding the Power of Position: A Diagnostic Model" in Organization Development: A Jossey-Bass Reader (2006); Michael Sales and Anika Savage, Life Sustaining Organizations (2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment